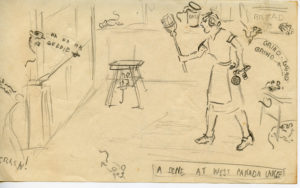

In November of 1926, Paul Bransom wrote a letter to an eleven-year old boy encouraging him to foster his artistic interests. In cartoons like “A Sene [sic] at West Canada Lake” of the eternal war with mice, George Allen Streeter demonstrated to Paul Bransom the young boy’s artistic talents.

Beyond the accomplished perspective drawing, Bransom would have appreciated the movement and expression of the mice captured with an economy of lines. He would have been amused by the defiance of the mice and the inability of the woman to control them. Central to Bransom’s representations of animals was his attempt to see them through their perspective and not that of the human. In pictures like his Spectator Fox, he took the perspective of the hunted and not the hunter.

Bransom accompanied the letter with a portfolio of his rough sketches. Paul and Grace Bransom were family friends of George Allen Streeter and his family at the Lake. George’s mother, Julia Allen Streeter, was an accomplished artist and looked to Bransom for advice and encouragement. The letter is striking in the respect and understanding that Paul Bransom showed to this young boy. At the letter’s core was Paul Bransom’s deeply held belief in an individual’s innate talents and his conviction that one should pursue these. He knew at an early age that he was destined to pursue an artistic career and more specifically a wildlife artist. He believed, ‘Animal Artists are born, not made. Doing animals is a compulsion, it is not something you go into because it pays well…. The real compensation is the excitement and pleasure of the doing!” Paul Bransom could see much of himself in the eleven-year old. Neither Bransom or Streeter pursued formal artistic training. They both based their work on continued practice and careful observation. The “compulsion” to create was in the “nature” of both men.

George Streeter maintained a friendship with Paul Bransom until the latter’s death in 1979.

Yearly illustrated Christmas cards from George to Paul attest to the close connection between the two. They communicated as two artists sharing their challenges and interests.

In his note on his 1973, Xmas card illustration, George Streeter refers to the same artistic issues one can see Paul Bransom dealing with in the portfolio of drawings sent forty-seven years earlier to the ten-year old boy. George wanted to animate the image with the motion of the fire that could be better brought out by making “the inside…more emphatic” with the contrast in light and dark. The expressive movement of the stone lintel echoes the movements found in Bransom’s illustrations. Movement and dramatic play of light and dark are important elements of Paul Bransom’s works.

George Streeter did not pursue a professional career as an artist. He became a highly respected member of the psychiatric community in Cleveland. But the artistic perspective was always at the core of his being. His proudest professional accomplishment was establishing the Art Therapy Studio of Cleveland, the oldest of its kind in the country. Like Bransom, George Streeter believed in the importance of discovering the artist within and the critical role this can play in wellness. George’s childhood connection with Paul Bransom had a life-long impact. In retirement George was able to dedicate his life to his true calling.

Green Lake P.O.

Fulton County

N.Y.

Nov. 14, 1926

Dear George Allen:

Last summer I promised to let you have my “practice drawings” for the horse pictures I was then doing. I meant to bring these across the lake to you and at the same time have the pleasure of a visit with your gracious mother and father and sisters (too two),[1] but several big commissions came along together and the pressure of trying to do everything at the same time prevented me from doing many of the other nice things I had anticipated. The wild horse rough sketches are here forwarded to you tomorrow under separate cover and I have added some others which I thought might interest you.[2]

We are still at the lake, quite comfortable despite an occasional ten above zero. I have some work to finish before I can break up to move.

We are leaving by the end of the week. I to go directly down to the swamps of southern Alabama to make some pictures of a wild cat hunt for the Curtis Pub. Co..[3] I’ll be back in about a week though and join Mrs. Bransom in Forest Hills Gardens, Long Island where we expect to be located this winter (114 Ascan Ave).

I trust that you are making fine progress with your drawings and that it will continue to interest you. Mrs. Bransom joins me with love and best wishes for you all and I am very sincerely your friend,

Paul Bransom

Drawings from the Portfolio sent by Paul Bransom to George Allen Streeter:

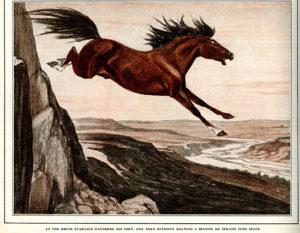

Three Studies for Starface Making his Leap:

Included in the portfolio were three studies for an illustration entitled “Starface Making his Leap” intended for a story by J. Frank Dobie entitled “Tales of the Mustang” (Country Gentleman, October, 1926, pp. 9 ff (illustration is on p. 10)). The subject of a mustang leaping off a cliff to avoid being captured connects to the theme of wildness, an underlying subject of Bransom’s works. It seems hardly coincidental that Bransom included these “horse pictures” in the portfolio. Horses were a regular subject in George Streeter’s works.

Included in the portfolio were three studies for an illustration entitled “Starface Making his Leap” intended for a story by J. Frank Dobie entitled “Tales of the Mustang” (Country Gentleman, October, 1926, pp. 9 ff (illustration is on p. 10)). The subject of a mustang leaping off a cliff to avoid being captured connects to the theme of wildness, an underlying subject of Bransom’s works. It seems hardly coincidental that Bransom included these “horse pictures” in the portfolio. Horses were a regular subject in George Streeter’s works.

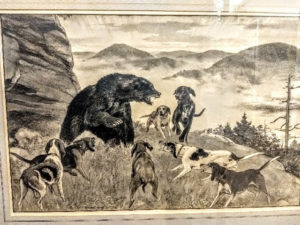

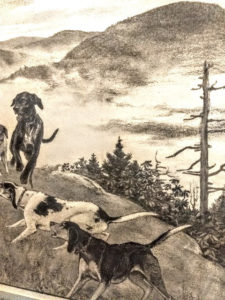

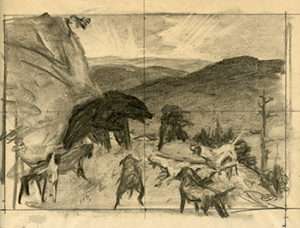

Two Studies for Cornered- Bear and Hounds:

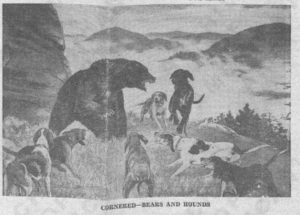

The story these sketches are connected to has not been identified, but the final work was a picture that Bransom apparently kept and exhibited a number of times. The photograph below comes from a May 21, 1942 New York Post article about a Paul Bransom exhibition at the Bronx Zoo. (for the clipping see no. 1 the Archives of American Art: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/paul-bransom-papers-8933/series-5/box-6-folder-17).[4] The noted animal artist Bob Kuhn, a long time friend of Bransom, mentions a “large charcoal drawing of a cornered black bear and hounds by Paul Bransom” that he saw in 1962 in the Latendorf Book Store in New York City (Bob Kuhn: Drawing on Instinct, edited by Adam Duncan Harris, p. 15).

The story these sketches are connected to has not been identified, but the final work was a picture that Bransom apparently kept and exhibited a number of times. The photograph below comes from a May 21, 1942 New York Post article about a Paul Bransom exhibition at the Bronx Zoo. (for the clipping see no. 1 the Archives of American Art: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/paul-bransom-papers-8933/series-5/box-6-folder-17).[4] The noted animal artist Bob Kuhn, a long time friend of Bransom, mentions a “large charcoal drawing of a cornered black bear and hounds by Paul Bransom” that he saw in 1962 in the Latendorf Book Store in New York City (Bob Kuhn: Drawing on Instinct, edited by Adam Duncan Harris, p. 15).

The final piece is currently in the John L. Wehle Gallery, a part of the Genesee Country Village & Museum in Mumford, New York which has given permission to use these images. John Wehle developed his collection around his interests in hunting, sports, wildlife, and conservation. John Wehle acquired Cornered from the Grand Central Galleries in New York City in 1974.

Comparison of the two sketches with the final version gives us insights into the artistic decisions Bransom made as he worked on a composition. He was aware of the importance of making a number of small preliminary sketches “realizing that any picture subject may be presented in a thousand different ways.” A part of his regular practice was the use of a grid. This both facilitated transfer and enlargement of a composition and also reminded him of the two dimensional surface of the composition, “giving special attention to the harmonious arrangement of the shapes of the areas involved.” In the second and more resolved drawing, Bransom places the snarling muzzle of the bear just above the absolute center of the composition. He raises the bear and the most distant dog higher on the picture plane and makes their poses more vertical. These changes enhance the dramatic confrontation of the bear and the dog. Comparison to the first drawing, shows how he has shifted the positioning of the foreground dogs to be coming more from the corners of the image to enhance the dramatic diagonals converging on the bear. These diagonals serve both to create a recession into depth and a dramatic compositional movement. Similarly he balances the rocky background on the left with the prominent tree in the middle ground on the right. This again creates a sense of plunging into depth and another strong diagonal movement across the composition reinforced by the sloping hill.

These small sketches also allowed Bransom to experiment with his use of light and dark so critical to his final images. Making the valley in the background in the second drawing lighter has allowed Bransom to bring out more dramatically the confrontation between the bear and the most distant dog. The snarling muzzle of the bear is dramatically silhouetted against the lighter background.

Two-Wolves Guarding Their Prey:

The destination of the final version of this preparatory drawing is not known. It exemplifies Bransom’s interest in the psychology and not just the physical form of animals. Yes he knew the anatomy of the animals he drew, but he also studied their characteristic poses. He encouraged quick drawings from life and moving on to a separate drawing when the animal changes poses. From practice over time, an astute observer will be able to isolate characteristic stances of an animal. In these different stances the psychology of the animal emerges. The wariness of the two wolves is brought out by their guarded stances and their fixed attention on the potential threat posed by the intruding observer.

The destination of the final version of this preparatory drawing is not known. It exemplifies Bransom’s interest in the psychology and not just the physical form of animals. Yes he knew the anatomy of the animals he drew, but he also studied their characteristic poses. He encouraged quick drawings from life and moving on to a separate drawing when the animal changes poses. From practice over time, an astute observer will be able to isolate characteristic stances of an animal. In these different stances the psychology of the animal emerges. The wariness of the two wolves is brought out by their guarded stances and their fixed attention on the potential threat posed by the intruding observer.

The beginning of James Oliver Curwood’s “Swift Lightning” (Cosmopolitan, 66, April, 1919, pp. 16 ff.)has a good comparison of the wolf to the dog. Contrasting Swift Lightning who is a mixed breed to a wolf, Curwood writes: “About him was little of the sneaking and cautious alertness of his brethern. He looked forth openly and unafraid. His back was straight, his hips free of the “wolf-droop,” and all over he was the soft and elusive gray of the gray brush-rabbit. His head had about it a massiveness that was strange to the wolf breed; his eyes were wider apart, his jowl heavier. And his tail did not not drag….” Bransom’s illustration accompanying the story captures this contrast between Swift Lightning as a mixed breed and the pack of wolves.

The beginning of James Oliver Curwood’s “Swift Lightning” (Cosmopolitan, 66, April, 1919, pp. 16 ff.)has a good comparison of the wolf to the dog. Contrasting Swift Lightning who is a mixed breed to a wolf, Curwood writes: “About him was little of the sneaking and cautious alertness of his brethern. He looked forth openly and unafraid. His back was straight, his hips free of the “wolf-droop,” and all over he was the soft and elusive gray of the gray brush-rabbit. His head had about it a massiveness that was strange to the wolf breed; his eyes were wider apart, his jowl heavier. And his tail did not not drag….” Bransom’s illustration accompanying the story captures this contrast between Swift Lightning as a mixed breed and the pack of wolves.

[1] George Allen Streeter’s parents were Julia Allen Streeter and George Linius Streeter. He had two sisters, Sally and Mary.

[2] The wild horse drawings were those created for J. Frank Dobie’s “Tales of the Mustang,” Country Gentleman, October, 1926, pp. 9 ff.

[3] Curtis Publishing Company’s publications included The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, and The Country Gentleman. Beginning in 1908, Paul Bransom was a regular illustrator for these journals, including doing both covers and the illustrations for stories. All Unplanned, pp. 150-1 describes his trip to the Tombigbee River in Alabama for a Bay Lynx or wildcat hunt. In March of 1927 his drawings from this trip appeared in an article by E.H. Taylor in Country Gentleman.

[4] Besides from the 1942 Bronx Zoo show, Cornered appeared in a December 16-January 4, 1929 show at the Warren E. Cox Galleries; a 1931 show at the Scribner Book Store in NYC; and in the 1942 Society of Illustrators exhibtion where it is listed as magazine illustration.